This article was written prior to the government’s announcement that all maintained secondary schools in England must have converted to academy status by 2022.

This article was written prior to the government’s announcement that all maintained secondary schools in England must have converted to academy status by 2022.

Professor David Hopkins is Professor Emeritus at the Institute of Education, University College London and Bright Tribe Professor of Education at the University of Bolton. With the recent publication of Exploding the Myths of School Reform (Hopkins 2013), David has completed his trilogy of books on school and system improvement. Here, he writes…

Turning schools into academies does not necessarily improve results; here are some approaches that work.

The dramatic expansion of the academies programme in England has been the major structural reform in education during the 21st century so far. Academies are, of course, self-governing non-profit charitable trusts directly funded by the Department for Education (DfE) and are independent of local authority control.

Reviews of student performance in academy chains are however ambivalent at best.

It is clear from the evidence that simply becoming an academy is not a panacea. We need strategies that not only continue to raise standards but also build capacity within the school and system (Hopkins 2013). One cannot just drive to raise standards in an instrumental way, by changing structures; one also needs to develop social, intellectual and organisational capital.

Building capacity demands that we replace numerous individual and idiosyncratic initiatives with a coherent and effective school improvement strategy that not only reflects the moral purpose of the academy chain but also is controllable, in organisational and financial management terms. This is what we attempted to do in designing and establishing Bright Tribe and Adventure Learning Academy Schools Trust (ALAT).

We must replace numerous individual and idiosyncratic initiatives with a coherent and effective school improvement strategy

The Bright Tribe and ALAT family of schools is a new MAT, with an unrelenting moral purpose to ensure that the schools create learning conditions that enable every young person to reach their potential – wherever that may lead. Our first conversion was in January 2014 and we now have 12 schools in the North West, Cornwall and Suffolk. The remainder of this article describes the main features of our approach.

Personalised learning

At the core of the Bright Tribe mission is a commitment to treat every learner as an individual and with respect, recognising that they have a unique set of gifts that it is our privilege to nurture. We are confident that this aim can be achieved through the rigorous application of the personalised learning and school improvement strategies that underpin the Bright Tribe and Adventure Learning approach.

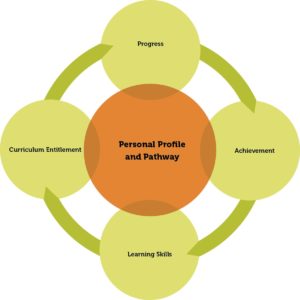

This moral purpose drives the approach that aims to deliver the following outcomes for all Tribe learners as illustrated in figure 1.

- Progress: all will make at least expected progress; with the aim that 70% of every cohort makes greater than expected progress.

- Achievement: all will achieve in line with national norms; and the great majority will outstrip this.

- Learning skills: all have a unique and personalised learner profile that will enable them to take control of their learning, understanding their areas of strength as well as areas to develop.

- Curriculum entitlement: all have a curriculum guarantee that means alongside an unrelenting focus on the core academic vocational subjects they will have access to a wide range of additional experiences. These will enrich their time at school and strengthen their view of themselves and their place in the world.

Whole school design

Bright Tribe is adopting a whole-school design that comprises six core elements (Bright Tribe 2014a). These six elements – leadership, personalised learning, curriculum frameworks, high quality teaching, partnerships and accountability – are the essential features of an outstanding school. Each is underpinned by a set of proven practices that will be consistently adopted across the family of schools.

School improvement pathway

As a result of our ongoing school improvement work (Hopkins 2013), we have gained specific knowledge about the combination of strategies needed to move a school and a system along the performance continuum towards excellence. Hence our adoption of a phased approach to school improvement; all of our schools are on an improvement journey that is intended to lead to excellence as shown in figure 2.

In our supporting materials, we outline the four phases of the performance continuum, describing what each aspect of the whole school design looks like at each phase of improvement. We identify the key issues that emerge at each step along the pathway, and suggest a series of questions to help progress development. These questions help school leaders to:

- complete an honest diagnosis of their school’s current performance

- prepare a plan for progress towards excellence.

The following provides a very brief summary of the appropriate intervention and support and the characteristics of each school type at each phase of development.

Getting on to the improvement pathway: these schools lack the capacity to improve. They need a high level of external support and direction in order to get the basics in place and to establish the preconditions for success.

Schools on the journey to good: these schools need to refine their developmental priorities, focus on specific teaching and learning issues, and build capacity within the school to support this work.

Getting to outstanding schools: in this phase of their journey schools need specific strategies that ensure the school remains a ‘moving’ school, continues to enhance pupil performance and engages in networking with Bright Tribe schools and others. The key issues here are about succession planning and developing staff at all levels.

Outstanding schools that sustain excellence: this is measured by the way in which they search for excellence internally and support other schools in their own journeys of improvement externally.

The primacy of teacher development

If our aspiration of personalised learning is to be realised, then schools need to be places where teachers and leaders learn as much as students. This is why Bright Tribe places such a high premium on teacher and leader development based on the following principles (Bright Tribe 2014b):

- All development is focused on the professional behaviours that reliably enhance the progress of students.

- Teacher and leader development is best achieved through the extension of individual professional skill within a collaborative setting. It also depends on the school and trust regarding professional growth and development, and accountability, as opposite sides of the same coin.

- Every teacher and leader within school is on a professional development pathway that leads to the extension of professional practice, is amenable to accreditation and can lead to the acquisition of a higher degree in conjunction with our partner HEI – The University of Bolton.

Building capacity

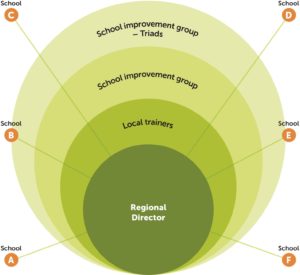

Capacity is built at the regional level to ensure that all those in the Trust’s family of schools progress as rapidly as possible towards excellence. Figure 3 illustrates how this works. In particular:

- Central to regional capacity building is the regional director or executive principal who provides leadership, develops the narrative and acts as the Trust’s champion in that geographic area.

- One of their key tasks is to build local capacity by training a group of lead practitioners in the Bright Tribe ways of working, materials and strategies.

- The training design used to develop trainers is the Joyce and Showers (1995) coaching model.

- These trainers then work with the school improvement teams in each school to build within-school capacity and consistency.

- Inter-school networking allows for authentic innovation and the transfer of outstanding practice, thus building the capacity of the network as a whole.

The three key aspects to this strategy – school improvement teams, staff development processes and networking – provide the focus for much of the training for our executive principals, as they play a critical role in systemic improvement.

The benefits of coaching teachers

Joyce and Showers found that coaching appeared to contribute to the transfer of training in five ways.

Coached teachers:

- practised new strategies more often and with greater skill

- adapted the strategies more appropriately to their own goals and contexts

- retained and increased their skill over time (uncoached teachers did not)

- were more likely to explain the new models of teaching to their students

- demonstrated a clearer understanding of the purposes and use of the new strategies.

From Joyce, B. R. & Showers, B. (2000) Designing Training and Peer Coaching: Our needs for learning, VA, USA, ASCD

In concluding

It is clear from international benchmarking studies of school performance (Hopkins 2013) and our experience that:

- Decentralisation by itself increases variation and can reduce overall system performance. There is a consequent need for some ‘mediating level’ within the system to connect the centre to schools and schools to each other – academy chains and MATs can provide this function.

- Leadership is the crucial factor both in school transformation and system renewal, so investment particularly in principal and leadership training is essential – hence the use of frameworks such as the whole school design and improvement pathway to guide action.

- The quality of teaching is the best determinant of student performance, so any reform framework must address the professional repertoires of teachers and other adults in the classroom – thus the focus in these trusts on the progress of learners and the development of teachers.

- Outstanding educational systems find ways of learning from the best and use the system’s diversity to good advantage – this is why capacity needs to be built not only within trusts, but also between them at the system level.

References

1. Bright Tribe Trust (2014a) Designing for powerful progress, Stockport, Manchester: Bright Tribe Trust

2. Bright Tribe Trust (2014b) High quality teaching for powerful progress, Stockport, Manchester: Bright Tribe Trust

3. Department for Education (2015) http://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/schools-in-academy-chains-and-las-performance-measures.

4. Hopkins, D (2013) Exploding the Myths of School Reform, Maidenhead, Berkshire: Open University Press.

5. Joyce, B. R. & Showers, B. (1995) Student Achievement through Staff Development (2nd ed.) New York: Longman

Read: Schools shouldn’t give in to the fear, but should be thinking hard about academisation.

Visit Professor David Hopkins’ website.