Since the turn of the calendar year, I have been responsible for SSAT’s offer for supporting schools in supporting student leadership. When I took on this role, I couldn’t have been more delighted because my first brief as a newly appointed assistant headteacher was to build our school’s student leadership offer. Exactly twenty years later, I was being asked to return to where my whole-school leadership journey started.

In fact, the parallels were even spookier because, when I managed to get a student parliament up and running at that school, the organisation I turned to for external training for our student leaders was SSAT. It felt like a case of serendipity, something I have always valued but which is often under-rated as a key component of how the complex business of leadership works.

One of the things I learnt back in 2005 as an eager young assistant headteacher was that the extant literature informing student leadership practice was firmly rooted in the civil rights movements of the 1960s. The focus, in those heady times and the decades that followed, was on giving the under-heard and under-represented and voice and a presence in decision-making.

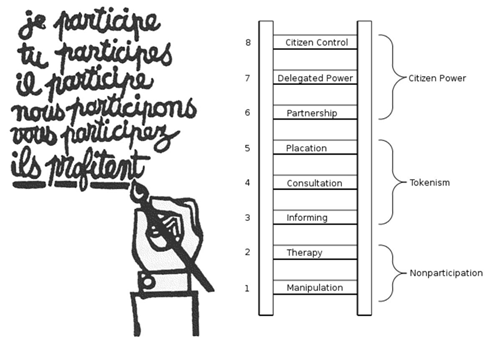

This focus on civic empowerment was apparent in the work of Roger Hart who adapted the civil rights’ era ‘ladder of citizen participation’ by Sherry Arnstein for UNICEF. Hart’s work was focused on how to involve children and young people in adult projects and programmes, up to and including the level of design and control of such programmes (moving beyond consultation). Published in 1992, it reflected the mood of the era in which the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) was ratified (1988) and adopted in the UK (1992).

Articles 12 and 13 of the UNCRC are particularly pertinent for thinking about student voice. Together, these guarantee the right to freedom of expression on matters affecting them with due weight paid to their age and maturity. It was for these reasons – reflected and refracted through other key researchers – that I developed a model of student leadership at that school that reached across multiple elements of the school’s work. Overseeing it all was the parliament that devised and revised its own constitution.

So, it was interesting for me, twenty years later to be back to the student leadership research literature to see what areas of inquiry had developed in the meantime. I have blogged about this previously and so I won’t repeat myself here. This link will take you to the key findings I have taken from this research and put into our revised ‘Student Leadership for IMPACT’ offer. There was, though, one piece of research that stood out which I want to explore here.

In 2008, Roger Hart published a follow-up piece to his work on a ladder of youth participation, called ‘Stepping back from the ladder’. In it he outlines several reasons why he wanted to take that step back. He felt that his initial paper lacked focus on every-day, informal participation. And critically, he felt that there was an over-emphasis on children’s empowerment engendered by the hierarchical nature of the ladder metaphor he had used. He concluded by saying:

“From my perspective, I see the ladder lying in the long grass of an orchard at the end of the season”.

Revisionism applied one’s own work is always a tricky business, and this cagey insight felt as risky for my previous understanding of student leadership as seems to be the case for Hart. He seems to be saying that the job of empowering students (as much as needed) had been done, perhaps through the successful adoption of the UNCRC? Or perhaps he is articulating a view that young people now know their horizons and so civic empowerment is unboxed enough.

If I am being more critical, of Hart’s initial paper and of my own initial approach to student leadership, it is that empowerment was (and remains) important but is not sufficient by itself. Empowering the disempowered only takes us so far because it sees student leadership as an essentially political endeavour when students see it primarily as a social endeavour. This is supported by the newer, much richer (although still small scale) research referred to in my previous post, research that is much more likely to involve the voices of young people than was paradoxically missing from earlier empowerment theories.

The most important lesson from the more recent seams of student leadership research is that it strongly suggests that social processes of leadership are of more interest (and use?) to young people than the abstract ideals to which they are often seen to lead. Thus, for young people, learning what leadership is and how it functions is more important that being a leader. Influence is more important than control. Team-oriented work is more important than individual action. The list goes on.

None of which is to say that the civil rights agenda that underpinned the birth of the student leadership movement is unimportant to how student leadership well into the 21st century should operate in settings such as schools. It is perhaps, though, a recognition that the conceptual model was never going to be sufficient for a mature model of citizenship for those still working their way towards adulthood.

Arnstein’s 1969 paper includes what we would now call an infographic. It seems that many researchers and practitioners of student leadership paid more attention to the image on the right (the ladder metaphor) than to the image on the left. For those of you not familiar with your French verb conjugation, this image suggests that when I, you (singular), s/he, we, and you (plural) participate, everyone (they) profit. This fits well with the social process approach to developing student leadership that we have been developing at SSAT this year.

It leads directly to our focus on Student Leadership for IMPACT, as our own infographic shows.

Our aim in our revamped and relaunched student leadership work is thus not to tell schools to what ends student leadership should work: it sees empowerment as a process and not a goal. To illustrate this, I recently visited a school where the headteacher was very clear with students about what they could and could not shape in the school. One area they ‘could not shape’ was around uniform as the headteacher believed that this was a matter for governors and school leaders. Student leaders were empowered in many other areas (more than I have seen at most schools) but knew, understood and respected where the boundaries lay on this issue. They were grateful for the clarity with which the boundary was drawn and felt more empowered, not less, for knowing where they stood.

This example demonstrates the importance of student leadership being contextual and aligned (not all schools will take the same approach) so that it can be professional and modelled (everyone focused on what they can influence and doing it well). All parties were incredibly thoughtful about what such boundaries mean for them, paying attention to ethics in exploring the decision. Most importantly, it helped student leaders prioritise their work into areas where they could (and very much did) have a significant impact on the life of their school.

I started this post by articulating the parallels between my student leadership work as a newly minted assistant headteacher and my recent work on developing SSAT’s offer to support student leadership in schools. But, as ever, when we move on we never return to find things as they once were: you can’t step in the same river twice, especially two decades later.

Instead, my return journey to understanding student leadership through considering its theory and its practice has shown me that the approach of schools should be (and often is) more nuanced than was the case previously with regard to the issue of empowerment. This approach reminds me of Hannah Arendt, who once wrote that power can only emerge between groups of people acting in concert in the public arena. It is fleeting and disappears when those groups no longer interact. It is unpredictable because it is contingent upon people, who are always unpredictable. Power can neither be given nor seized but emerges through social processes.

For schools looking to develop their student leadership so that students are empowered, the starting point is those social processes, not a concept of power (however positively framed). Collaborative professional development of the staff leading in this area. Professional learning for groups of student leaders themselves. Recognition for schools and particularly for student leaders. Building strong networks and partnerships for student leadership across schools. All of these are vital, and all are now part of SSAT’s offer around Student Leadership for IMPACT.

If you would like to know more, click on the links in the previous paragraph, or book a call with me. It would be great to hear from you.

Jacqui on said:

This post really opened my eyes! It’s so powerful that leadership isn’t just about giving students a voice, and it shouldn’t be limited to formal roles. Incorporating everyday, informal participation means leadership becomes part of the school’s rhythm, not an occasional event. By seeing leadership as a social, lived experience, not just a political structure, we empower young people in more meaningful, authentic ways. This approach truly reshapes how we nurture future leaders.