Pasi Sahlberg is, along with Eric Mazur, Tony Wagner, Tony Wagner, Lord Baker of Dorking and Edge Foundation, Sherry Coutu and David McQueen, a keynote speaker at this year’s SSAT National Conference. In this guest blog, he explores some of the factors that have helped the Finnish education system deliver high quality and high equity outcomes for learners. At the conference, he will take this analysis wider with his session on the global education reform movement and its effect on the learner.

Pasi Sahlberg is, along with Eric Mazur, Tony Wagner, Tony Wagner, Lord Baker of Dorking and Edge Foundation, Sherry Coutu and David McQueen, a keynote speaker at this year’s SSAT National Conference. In this guest blog, he explores some of the factors that have helped the Finnish education system deliver high quality and high equity outcomes for learners. At the conference, he will take this analysis wider with his session on the global education reform movement and its effect on the learner.

Many have asked me what has made Finnish schools so successful. I answer by saying that success – good learning outcomes, participation rates and efficiency combined with system-wide equity – is a result of systematic attention to social justice and early intervention to help those with special needs. Close interplay between education and other sectors, particularly health, social and youth sectors, is typical in Finnish society. Furthermore, complimentary school lunches, comprehensive welfare services, and early childhood education and care for all children are also important.

School education should be put in the wider context and seen as a part of the overall function of democratic civil society

My advice to those trying to explain the success of the education system in Finland is that school education should be put in the wider context and seen as a part of the overall function of democratic civil society. The quality of a nation – or its education system – is rarely a result of any single factor. Finland is a good example of this: the entire society needs to perform well.

Education policies that have driven Finnish reforms since the 1970s, have prioritised creating equal opportunities, raising quality, and increasing participation within all educational levels across Finnish society. As a result, more than 99% of the age cohort successfully completes compulsory basic school, about 95% continue their education in upper secondary schools, and an additional 3% enrol in a voluntary 10th grade of basic school. About 95% of Finns eventually receive the secondary education certificate that provides access to higher education.

Equity in education is an important feature in Nordic welfare states. It means more than just opening access to an equal education for all. Equity in education is a principle that aims at guaranteeing high-quality education for all in different places and circumstances. In the Finnish context equity is about having a socially fair and inclusive education system where children’s learning in school is less determined by their family background. As a result of the basic school reform of the 1970s, education opportunities for good quality learning have spread rather evenly across Finland. Clear evidence of more equitable learning outcomes came from the OECD’s first PISA survey in 2000. In that study, Finland had the smallest performance variations between schools in reading, mathematics, and science of all OECD nations. A similar trend has continued in all PISA studies since then.

An essential element of the Finnish comprehensive school is systematic attention to those students who have special educational needs

I think that an essential element of the Finnish comprehensive school is systematic attention to those students who have special educational needs. Special education is an important part of education and care in Finland. It refers to designed educational and psychological services within the education sector for those with special needs. The basic idea is common sense: detect learning difficulties or behavioural problems as early as possible and then provide targeted support immediately.

A new special education system in Finland since 2011 is defined under the title of Learning and Schooling Support and all such students are increasingly integrated into regular classrooms. There are three categories of support to those pupils possessing special needs: (a) general support, (b) intensified support, and (c) special support. The first includes actions by the regular classroom teacher in terms of differentiation as well as efforts by the school to cope with student diversity. The second category consists of remedial support by the teacher, co-teaching with the special education teacher, and individual or small group learning with a part-time special education teacher. The third category includes a wide range of special education services from full-time general education to a placement in a special institution. All students in this category are assigned an Individual Learning Plan that takes into account the characteristics of each learner and thereby personalises learning to meet each learner’s abilities. As a consequence of this renewed special education system the number of students categorised as special needs students will decrease.

Most [Finnish] schools pay very particular attention to those children who need more help in becoming successful

I often hear that Finland’s special education system is one of those key factors that explain world-class results in achievement and equity of Finland’s school system in recent international studies. My personal experience, based on working with and visiting hundreds of Finnish schools, is that most schools pay very particular attention to those children who need more help in becoming successful, compared to other students. Many teachers and administrators who have visited Finnish schools think the same way but are often stuck in the middle of excellence vs. equity quandaries due to external demands and regulations in their own countries. Standardised testing that compares individuals to statistical averages, competition that leaves weaker students behind, and merit-based pay for teachers all jeopardise schools’ efforts to enhance equity. None of these factors currently exist in the Finnish education system.

How many students have special needs in Finland? Since 2011 only those students who receive intensified or special support in school are considered as special needs students. In school year 2012-2013 in basic school 12.7% of students were included in this new type of special education, 7.7% received special support and 5% intensified support. Almost one third of students received some kind of learning and schooling support in 2012-2013. In vocational upper-secondary education, approximately 14.3% of all students were in special education during the school year 2012–2013.

Finnish education today offers a compelling model because of its high quality and equitable student learning

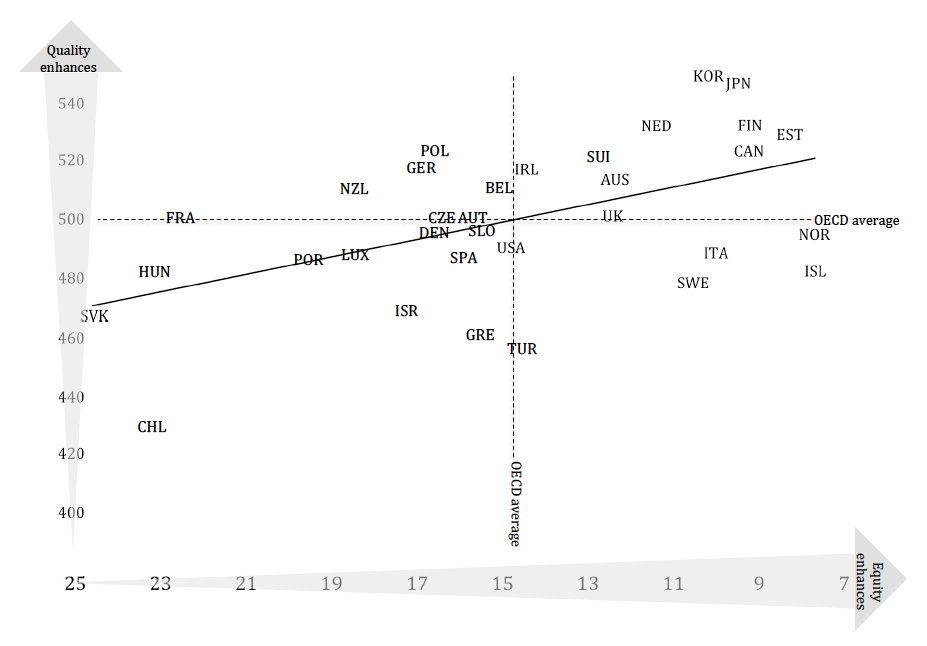

Unlike many other school systems today, the Finnish system has not been infected by market-based education reforms that typically emphasise competition between schools and high-stakes standardised student-testing. The main reason is that the education community in Finland has remained unconvinced that competition and choice with more standardised testing than students evidently require would be good for schools. As a result, Finnish education today offers a compelling model because of its high quality and equitable student learning. As the figure below shows, Finland, Canada, Estonia, Japan, and Korea have education systems that rate highly in quality and equity; they produce consistent learning results regardless of students’ socioeconomic status.

Figure: Equity and quality of education outcomes (mathematics)

Figure: Equity and quality of education outcomes (mathematics)

Although educational success in Finland is not a result of educational factors alone, there are lessons that the UK can learn from Finland. The first lesson is about the importance of equity for the overall quality of an education system. Finnish experience shows that systematic focus on enhancing equity in education may lead to improved quality of learning of all children. The second lesson is about more intelligent accountability and assessment policies for schools. Finnish schools prevent children from being ranked according to their educational performance in schools, grade-based assessments are not normally used during the first five years of primary school. It has been an important principle in developing elementary education in Finland that structural elements that cause student failure in schools should be removed. Finally, Finland offers an alternative model of early childhood education to policymakers in the UK that gives play a central role in children’s development and learning. Many Finnish educators and parents alike think that to start formal learning too early in a child’s life is to ruin natural curiosity and creativity.