Reading time: 3 minutes. Relevant download: Mental health flow chart

SSAT Leadership Legacy Fellow Dayne Meakin and PE teacher, Bishop Walsh Catholic School writes

Mental health issues are one of the largest threats to people across Europe (World Health Organisation, 2005), which is having significant negative impacts on children in education. A 2016 report from DfE found children who have issues with their mental health will make less progress in school. Here are my suggestions to improve mental health provision in school, which involves gaining information on how teachers feel they are equipped in promoting positive mental health as well as dealing with students when they have mental health issues.

It has been documented that one in 10 children under age 16 has been diagnosed with a mental health disorder, and one in seven have mental health issues that are less complex (DfE, 2016). Rones and Hoagwood (2000) explore these negative effects and identify social burdens that could also be harming young people’s mental health.

A commonly expressed view is that schools should be at the forefront of the initial fight against mental health issues, with headlines such as “Children’s mental health services are struggling. Can teachers help?” (Bennett, 2016) and “Mental health must be a priority in schools, says MP” (Dixon, 2016). The 2016 DfE report stated that schools are in the prime place to recognise the development of mental health issues as they see students on a daily basis, can recognise changes in their behaviour, and are well placed to teach and promote positive mental health. However, previous research highlighted that teachers feel they have a lack of knowledge about mental health and do not feel confident in addressing such sensitive issues (Best, 1999; Watson-Davis, 2005; Tubbs, 2012).

While we have to realise that the main role of a school is to educate students and not to be mental health specialists, it is clear that we need to be able to support students more, so that mental health issues do not develop into mental health disorders.

Students with severe mental health issues are referred by their doctor to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS). However, due to the high volume of referrals to CAMHS (Thorley, 2016), the service can struggle as it has never been resourced well enough to deal with the demand (Ford et al., 2008). This report suggested that if teachers, parents and GPs understood more about the nature of mental health, it might lead to more effective use of the service as many of the referrals would be more appropriate. It is possible that if the volume was lower and if the education for people who make the decisions about getting help for children with mental health issues was improved, CAMHS may be more effective as their services would not be so stretched.

The CAMHS service cannot cope with current high volumes of referrals, so schools need to develop their understanding and more appropriate referrals

Many teaching staff in school have received little to no training on mental health. Some of those I have discussed this with say that the little knowledge that they have on this topic has come from either personal experience (family member etc), personal research stimulated by a student having issues, or from the media (TV programmes. etc). Most of these teachers felt that they were unprepared to deal with the volume and complexity of mental health issues and would like further guidance on it.

Stimulated by this need, I researched policies and frameworks and worked with the school’s head of pastoral care to develop a framework fit for our school.

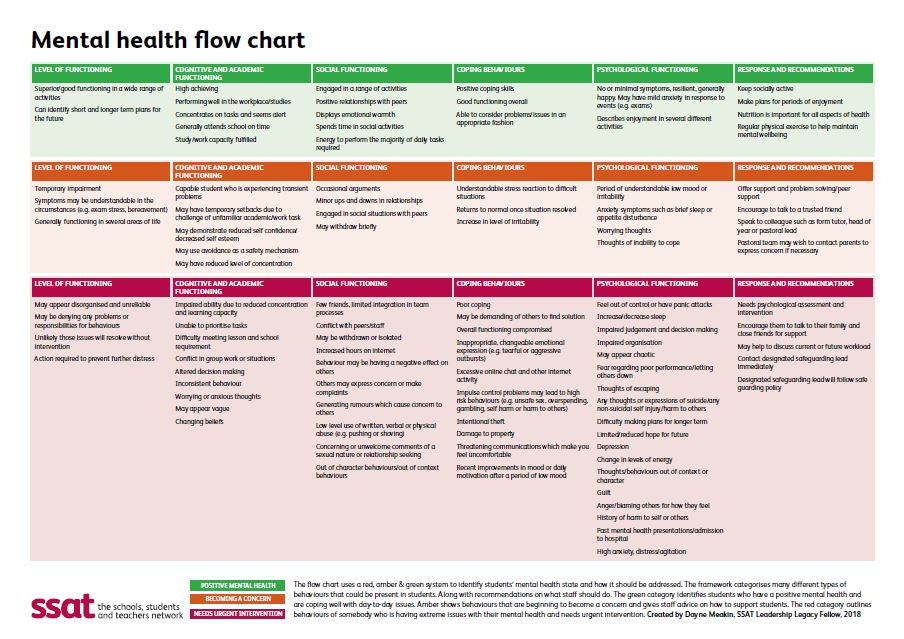

DOWNLOAD MENTAL HEALTH FLOW CHART

The flow chart uses a red, amber & green system to identify students’ mental health state and how it should be addressed. The framework categorises many different types of behaviours that could be present in students. Along with recommendations on what staff should do. The green category identifies students who have a positive mental health and are coping well with day-to-day issues. Amber shows behaviours that are beginning to become a concern and gives staff advice on how to support students. The red category outlines behaviours of somebody who is having extreme issues with their mental health and needs urgent intervention. Staff who have seen this framework believe it is a very useful tool, and it is simple to read and easy to use for somebody who has little knowledge about what to look out for.

I have also adapted a policy from Dr Pooky Knightsmith, who is a child and adolescent mental health expert. I have proposed that this policy works in conjunction with the school’s current safeguarding policy.

References

- Bennett, T. (2016). Children’s mental health services are struggling. Can teachers help? Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/healthcare-network/2016/dec/09/childrens-mental-health-services-are-struggling-can-teachers-help

- Best, R. (1999). The Impact of a Decade of Educational Change on Pastoral Care and PSE: A Survey of Teacher Perceptions, Pastoral Care in Education, 17(2), pp. 3-13.

- Department for Education (2016). Mental health and behaviour in schools departmental advice for staff. London: Department for Education.

- Dixon, J. (2016). ”Mental health must be made a priority in schools”, says MP. Available at: https://www.londonnewsonline.co.uk/13160/mental-health-must-made-priority-schools-says-mp/.

- Ford, T., Hamilton, H., Meltzer, M., and Goodman, R. (2008). Predictors of Service Use for Mental Health Problems Among British Schoolchildren, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Volume, 13(1), pp. 32-40.

- Rones, M., & Hoagwood, K. (2000). School-based mental health services: A research review,

Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 3, pp. 223–241. - Rush, A.M. (2012). What are the experiences of young people who, following their discharge from child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS), do not transfer into adult mental health services (AMHS)? Thesis for a Degree of Doctorate in Clinical Psychology. University of Birmingham

- The World Health Organisation (2005). Mental Health: Facing the Challenges, Building Solutions. World Health Organisation: Geneva.

- Thorley, C. (2016). Education, education, mental health: Supporting secondary schools to play a central role in early intervention mental health services. London:IPPR.

- Tubbs, N. (2012). The New Teacher: An Introduction to Teaching in Comprehensive Education. London: Routledge.

- Watson-Davis, R. (2005). Form Tutors Pocketbook. Hampshire: Teachers Pocketbooks

Dayne Meakin was part of the first SSAT Leadership Legacy Project cohort 2017/18. A second year-long initiative for 2018/19 and has been set up once again to develop teachers identified by their headteacher as having the potential to become outstanding leaders. Nominations for the second cohort are open Monday 3 September to Wednesday 19 September 2018 – find out more and nominate now.

Read on the SSAT blog: How do we improve children’s mental health and wellbeing? Get them active!

Follow Dayne Meakin on Twitter

Follow Dayne Meakin on Twitter

Melanie Stubbs on said:

Excellent, helps staff to support students and look out for early signs before the situation grows out of proportion. This will be shared with the staff in my school.